Nora Eisner is an astrophysicist affiliated with KU Leuven’s Astronomy Unit. For her PhD at the University of Oxford, she is assisted by more than 30,000 volunteers. “I would never have been able to present such great results without those enthusiastic citizen scientists. Together we discover exoplanets that are missed by the most advanced algorithms.”

Are we alone in this universe? It’s one of the primordial questions us humans are asking themselves, and it explains not only the popularity of alien movies, Nora Eisner says, but also the sheer numbers of volunteers involved in space exploration. “On the online Zooniverse platform alone, there are 91 projects to which citizen scientists contribute. One of them is Planet Hunters, which presented its participants with data from the NASA Kepler space telescope and let them search for exoplanets, so planets orbiting a star other than our sun. I personally felt lucky that Planet Hunters was so successful because that way, I knew that coordinating a similar citizen science project would not be risky.”

Eisner’s project is named Planet Hunters TESS, and refers to the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which launched aboard a NASA rocket in April 2018. Ever since, it has been scanning an entire piece of sky every 30 days. It monitors the brightness of the stars in it, searching for dips in this brightness that could indicate that something is blocking out some of the star’s light. And that ‘something’ could be an exoplanet.”

20 million classifications

Interestingly enough, in this fascinating quest, the most advanced computers often loose out to the human eye for certain types of planets. “The automatic algorithms and smart tools with which we scan the sky require at least two dips to mark an exoplanet, while for our brain, one dip is enough. As a result, we fill an important niche with citizen science.”

“In addition, that one dip can point to something very interesting: exoplanets with a longer orbital period – longer than the satellite’s thirty days – which, as a result, could, potentially, place it in the habitable zone. This has to do with the distance from the star, through which planets potentially harbor water and thus life. That too is of course a quest that appeals to the imagination of many, adding to our project’s appeal for many citizen scientists.” Approximately 32,500 of them now make up the Planet Hunters TESS community.

“Consequently, we have somewhere between 40,000 and 70,000 light curve classifications completed per day. Since the start of the project in 2018, we have already created more than 20 million classifications together – an amount that would be unmanageable for me to look through by myself, or even for a whole research team.”

Contrary to what skeptics might think, the contribution of citizen scientists is also very reliable, says the Swiss-British astrophysicist. “As soon as you register and enter the online platform, a tutorial teaches you how to spot and indicate dips in brightness that correspond to transiting planets. In addition to seeing real data, you are intermittently shown simulated data, which also important to note is that each light curve is seen by fifteen citizen scientists, and we trust that if there is a real signal in the data that the majority will be able to identify it.”

Outstanding community

Eisner enthusiastically continues explaining the intricate way of working. “I designed an automated algorithm that combines the classifications from all of the the fifteen volunteers who saw each light curve in order to identify signals that multiple citizen scientists marked. The algorithm assumes that if more people identify the same signal, the signal is more likely to be real. For each signal, we then calculate a score – indicating how likely we think that the signal is real – which allows us to rank all of the light curves from most to least likely to contain a transiting planet.”

“The top 500 highest ranked candidates are then further investigated by the Planet Hunters TESS science team in order to determine whether the signal is real or caused by something other than an exoplanet, such as an asteroid. For this investigation, we run a large number of different diagnostic tests that helps us rule out these false positive scenarios.”

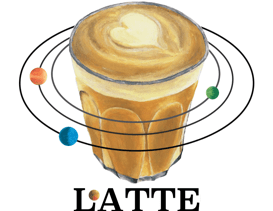

“We even encourage citizen scientists to run these kinds of test themselves, using a tool I developed: LATTE. It stands for Light curve Analysis Tool for Transiting Exoplanets and secretly refers to my love for coffee,” she smiles. “It’s great to see how many people have already downloaded it and are discussing their results on our forum. Seeing the LATTE diagnostic plots posted on the Planet Hunters TESS discussion forums really speeds up the process of identifying real new planets.”

“I also want to give back to our outstanding community of citizen scientists and I want to make science accessible to anyone who wants to take part. The project is designed such that anyone, from anywhere around the world and with any educational background, can take part. Anyone can help us identify a dip in the data – possibly corresponding to a new planet! – and can therefore contribute to real science.”

“It’s equally important to me that the Planet Hunters TESS community is diverse. As such, I am working with a team based at NASA Ames in order to provide knowledge and tools to the citizen science community and to help encourage anyone, regardless of their demographic, to join the search for new planets.”

60 co-authors

Open access and being transparent: those are key words for Eisner. “In order for science to advance, I think it is very important for the community to be open and transparent with their work. Within the exoplanet community we have great platforms to post new planet candidates, list your follow-up observations and indicate that you are working on a specific target. Similarly, my LATTE program is completely open access, and the whole Planet Hunters database is publicly available to anyone. Additionally, my recent collaboration with a team based at NASA Ames aims to provide YouTube how-to videos and code so that anyone can get involved with the science.”

“A project’s survey conducted in 2019, showed that the majority of our citizen scientists do not have a university degree themselves. But they find space research exciting and want to be involved. Some even do the analysis with their children, who have proven to be very good at identifying the small dips in the data that could correspond to a planet. I think looking for exoplanets is quite exciting because we can all picture what a planet looks like – we are living on one after all. For one of the more recent Planet Hunters TESS discoveries we looked into what the planet might look like in order to have an artist’s impression drawn up.”

“I think a lot of people – including me – want to give the planets that they find more imaginative names than the ID numbers that they now come with. Unfortunately, we’re not allowed to do that. However, we do invite the citizen scientists who are directly involved with identifying a planet candidate to become co-authors of any papers that are written about it. So far, we have over 60 citizen scientist co-authors on Planet Hunters TESS discovery papers.”

“The first planet that we found on the platform has the unimaginative name TOI 813b and it’s a planet that takes around 84 days to orbit around a slightly evolved star. This is particularly exciting because it allows to investigate what happens to planets – including our own Earth – as they age alongside their stars.”

Convincing results

“The advantage of having over 30,000 pairs of eyes visually inspecting the TESS data is that you sometimes find things you weren’t necessarily looking for. We recently came across a system which contains three massive stars orbiting around one another very rapidly. So even though there are no exoplanets, this is a very exciting system to analyse. This work was carried out with researchers at KU Leuven, where I spent some time as a visiting scholar last year, and it will soon be published. This only adds to the impressive track record which Planet Hunters TESS already has with three confirmed planets and over 120 planet candidates.”

“I’m very happy with what we have obtained so far”, Eisner concludes, “and I hope that these results are enough to convince anyone who still has doubts about the value of citizen science. We have shown that with citizen science we can obtain new and exciting results that differ from what the automated algorithms can do. Moreover, it is fun to work with such enthusiastic people and to hear positive feedback on the project. We, for our part, cannot thank them enough. Each of those 20 million classifications is invaluable to the project to further our understanding of what the planets in our galaxy look like.”

SOURCE: KULEUVEN

Categories: Breaking News, Leadership in Space